Spend any time in a printshop and you'll quickly discover that press operators, and even print buyers, depend on their loupes to help inform them about the quality of plates, proofs, and presswork.

This is a quick guide to help you choose the correct instrument for your needs. Beside each type of loupe/microscope is an image to approximate the view through that instrument. Keep in mind that all loupes and microscopes have limitations based on the laws of optics and that prices can vary widely. That is why having more than one instrument is usually best. In general the higher the magnification the smaller the field of view, the shallower the depth of view, and the closer the instrument must be to the subject. A single lens is satisfactory for low power loupes but higher power ones require two or more lens elements for improved resolution and correction of chromatic aberrations, distortion, and improved flatness of field (i.e. the entire viewed area appears in focus rather than just a small area in the center of the view).

Wide field comparator - 2x-6x ~ $50-$100

As its name implies, comparator loupes are typically used to compare two items, e.g. proof to press sheet, different paper surfaces, halftone screening methods, proof reading, etc.

Pros: Long eye relief coupled with a wide, flat field of view allows it to be shared by more than one viewer at a time without moving the loupe. Cut-away base allows room for touch-ups or mechanical changes to the item under inspection. Can be used to evaluate large scale issues such as halftone rosette structures and paper/ink mottle.

Cons: Rather limited applications in prepress/press relative to the cost. Low magnification does not reveal halftone quality issues.

Linen tester/folding loupe - 2x-10x ~ $25

This is the iconic press operator's loupe.

Use: Good for checking registration and macro imaging problems like rosette structure integrity and mottle.

Pros: Inexpensive, portable, easily available.

Cons: Low magnification does not reveal halftone quality issues. No focus adjustment.

Folding loupe (a.k.a. Hastings loupe, Hastings Triplet, Swing Loupe) - 10x-25x ~ $70

This is arguably the type of loupe actually most used by press operators. Highly recommended as a good all 'round basic loupe.

Use: Good for checking registration and macro imaging problems like rosette structure integrity and mottle. Higher magnification begins to identify issues such as slur and doubling.

Pros: Relatively inexpensive, portable.

Cons: None.

Rigid loupe - 10x-75x ~ $650

This magnifier is sometimes used in the press room but is more often used by a Quality Assurance Manager. Very flexible in that it can be customized with different lens options.

Use: Good for checking registration and with higher magnification, to identify issues such as slur and doubling.

Pros: Optional lenses can customize unit for specific shop needs. May come with color filters to enhance the visibility of dot structures. Built-in light.

Cons: Very expensive.

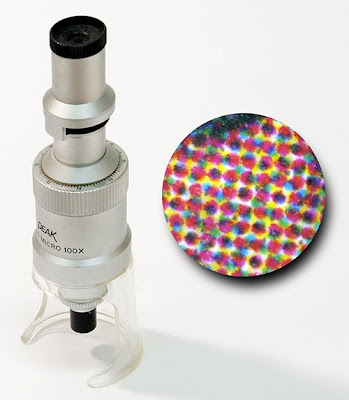

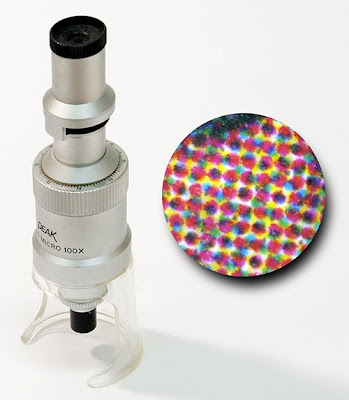

Pen microscope - 25x-100x ~ $100

This magnifier can be used in the press room and prepress. 50X is most popular - 75-100x is very good for checking FM screening. An excellent all 'round high magnification tool.

Use: Very good for identifying imaging issues such as slur and doubling.

Pros: Convenient pocket size. Can be focused by manually tilting it but can be difficult to hold steady.

Cons: Expensive.

Lab-type microscope - 25x-100x ~ $250

This magnifier tends to be more often used by a Quality Assurance Manager in a lab setting. 75-100x is most popular and very good for checking FM screening.

Use: Very good for identifying imaging issues such as slur and doubling.

Pros: Built-in measuring reticle scale is helpful in analyzing halftone structures.

Cons: Expensive. Typically produces an inverted view.

Digital video microscope - 20x-200x ~ $125

This magnifier tends to be more often used by a Quality Assurance Manager in a lab setting. 200x is most popular and is ideal for checking FM screening as well as detailed analysis of halftone issues. A must-have for any print/prepress shop.

Use: Excellent for identifying imaging issues such as slur and doubling and analyzing halftone reproduction issues. Ability to take photos and videos of halftones and other micro-features enables better record keeping as well as remote diagnostics. Build-in light helps with image quality. Software may be included for more detailed image analysis.

Pros: Still and video image capture. High magnification. Ability to process images with image analysis software. Ability to document and share image capture. Relatively inexpensive.

Cons: Must be tethered to a computer.

Where to buy

Shops that sell binoculars/telescopes, collectibles/stamps, and hobbyist supplies will also carry a selection of loupes and microscopes.

If your local shops can not source what you need - online sources include: http://www.edmundoptics.com, http://www.betascreen.com, http://www.amazon.com, http://www.ebay.com/

Addendum

Addendum

A reader, "Otherthoughts" described some of his experiences with the lab-type and pen microscopes.

"Regarding inversion and some background about why this was/is important to me.

I used a 25x scope like this for inspecting things a little closer during my press-man/press-room days.

Mine had a metric measuring reticle in it. Sometimes I would break this scope out and measure how far off the register marks were and then I would input the distance corrections into the press control unit. On the next pull, the marks would be almost perfectly registered. I only did this when the register marks were way off and/or I wanted to impress someone. The main reason I didn't use the scope more often as a Pressman, was because of it's inverted view. It's a pain to keep mumbling to yourself "left is right and up is down" when using this type of scope.

Without exception, every single stand/pen microscope that I've ever looked through at a trade show or that a vendor has shown to me in the press-room, has produced an inverted view as well. I always wanted to buy a right reading stand microscope of 25x or more, but I've never found one.

I know things have changed quite a bit since my days in the field. Nonetheless, there will still be directional components to the things that will be evaluated using these microscopes, e.g. slur, doubling, etc. and you will likely still have to remind yourself that "left is right and up is down" while evaluating their cause, meaning and remedies."

Thanks for the contribution Otherthoughts!

It contained two manually controlled light sources by which the client could select a certain temperature light at which the transparency pleased him.

It contained two manually controlled light sources by which the client could select a certain temperature light at which the transparency pleased him.